Capitalism and conflict at the margins: Why online scams flourish in Myanmar’s borderlands

In their new research initiative, The Centrality of the Margins, Xu Peng, Jonathan Goodhand, Patrick Meehan and Naomi Yonder ask what explains the concentration and resilience of scam compounds in these remote, war-affected regions. Here, they outline the issues and discuss the working hypotheses.

Imagine this: a new tech start-up is taking off. Like many others, it’s clustered in a booming region, with a multinational team working long hours in a sleek compound equipped with offices, dorms, shops, entertainment and other amenities. It may sound like a familiar story from San Francisco, or even East London, but it’s not. This is actually a story of fraud, coercion, and digital exploitation, unfolding in the borderlands of Myanmar, along the frontiers with China and Thailand.

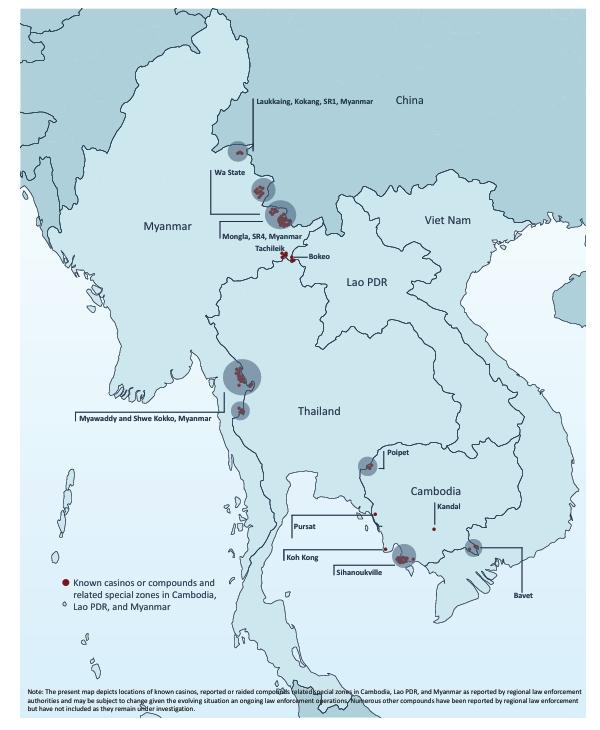

Over the past 5-years, these regions have become global hubs for online scam operations (Figure 1). While the exact number of scam compounds is hard to verify, an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 people are working in scam centres across Myanmar — many of them trafficked or coerced. Victims around the world are lured into fictitious investment opportunities or romances– a process euphemistically called ‘pig butchering’ – building trust like ‘fattening’ an animal before the financial ‘slaughter’.

Many workers were first recruited with promises of well-paid tech jobs in Thailand. But instead of landing start-up gigs, they were trafficked across the border into Myanmar’s militia-controlled zones. There, they are forced to work 16 hour days under armed guards to meet brutal profit quotes.

The conditions of exploitation and violence are not so different in many ways from the nineteenth-century opium factories in Bihar that Amitav Ghosh writes about in the first of his Ibis trilogy, the ‘Sea of Poppies’.

This raises urgent questions. What explains the concentration and resilience of scam compounds in these remote, war-affected regions? What makes this industry so rooted here — and not elsewhere? Surely online scams could thrive anywhere with digital infrastructure and weak regulation. So why the Myanmar borderlands?

These are the questions at the heart of our new research initiative, The Centrality of the Margins: Borderlands, illicit economies and uneven development. While we don’t yet have all the answers, we do have some working hypotheses — and they all point to the ways in which digital criminality, armed governance, and global capitalism intersect in Myanmar’s border zones.

Contested borderland histories and new digital spaces

Firstly, there’s a long backstory. Myanmar’s borderlands have long existed at the edge of state authority — shaped by decades of armed conflict, illicit trade, and fragmented rule. Control in these regions has shifted and overlapped between the Myanmar military, ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), and a patchwork of militias, including Border Guard Forces (BGFs), that are formally aligned with the military but often operate with significant autonomy.

Today, these same areas have evolved into digitally contested zones — where national laws around cybercrime have limited reach, and traditional forms of sovereignty lose traction.

Despite new cybercrime legislation in China (2022), Thailand (2023), Cambodia (2022), and Myanmar (2025), enforcement often stops at the border. The borderlands remain a digital power vacuum, where scam compounds operate with minimal fear of legal repercussions. This is not accidental.

The digital infrastructure of the scam industry — including unregulated internet access, crypto payments, and telecommunications — is built on pre-existing political autonomy and sustained by informal cross-border logistics. Here, digital governance breaks down, and neither host states nor neighbouring powers can intervene without political costs or exacerbating armed conflict.

Armed groups, revenues and innovation

Secondly, online scam compounds have become a critical revenue innovation for armed groups in Myanmar’s borderlands, especially state-linked militias and ‘BGFs’ that have links to Chinese crime syndicates and the Myanmar military. These groups have long relied on extractive industries such as drugs, jade, and logging to fund their operations — but online scams represent a shift from resource-based to people-based accumulation, enabled by both digital control (to scam victims around the world) and territorial control (to exploit workers within the compounds).

What gives these scams their staying power is not just their profitability, but their embeddedness in existing borderland infrastructures, including protection by armed groups, reliance on cross-border trafficking networks, and access to informal financial systems.

What gives these scams their staying power is not just their profitability, but their embeddedness in existing borderland infrastructures, including protection by armed groups, reliance on cross-border trafficking networks, and access to informal financial systems.

This is not simply a continuation of illicit economies, but a strategic evolution. Scams allow these groups to diversify income while minimising reliance on physical commodities. In doing so, they reinforce their political authority over both territory and people, not despite, but through, their adaptation to the digital age.

Compound capitalism, connecting war economies and peace economies

Thirdly, scam centre economies in Myanmar’s borderlands complicate the idea of a straightforward relationship between illicit economies and armed conflict – they have flourished in periods of war, peace and the grey areas in between. Sometimes they emerge as a byproduct of instability; other times, they act as catalysts for political change — influencing political alignments, security arrangements, and cross-border negotiations.

What sets scam economies apart is their strategic ambiguity. Armed actors use them flexibly: to extract rents during conflict, consolidate control under ceasefire, or gain leverage in political negotiations — particularly with external powers like China, where most victims are located. At the same time, the presence of scam hubs can generate new frictions, attracting enforcement pressure and triggering retaliatory violence or displacement.

In this sense, scam economies do not just span periods of war, ceasefire, and peace — they are part of the machinery that produces, blurs, and reconfigures the temporal boundaries between these categories. They signal a form of super-hybrid governance, where illicit digital accumulation coexists with armed coercion and political bargaining.

Scam centres are also a bridge between war and peace in a second – spatial – sense: they connect conflict zones with peace zones in a deeply symbiotic relationship– the ‘pigs’ to be ‘butchered’ do not live in war zones, they come from places and regions like China, Australia or Europe. This form of ‘Compound capitalism’ reveals a deeply entangled relationship between war economies and peace economies, margins and metropoles, the ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ worlds.

Studying Illicit economies like those emerging in Myanmar’s borderlands doesn’t just tell us about crime or conflict – it offers a window into how contemporary capitalism function at its edges, who it serves, and the social and political wreckage it leaves behind.

Image credit: Photo by Alexander Schimmeck on Unsplash

About the authors

Dr Xu Peng is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for the Study of Illicit Economies, Violence and Development (CIVAD), SOAS University of London.

Jonathan Goodhand is a Professor in Conflict and Development Studies in the Department of Development Studies, SOAS, University of London.

Dr Patrick Meehan is a Lecturer in Peace and Conflict Studies in the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute at the University of Manchester.

Naomi Yonder is a postgraduate student in MSc Humanitarianism, Aid and Conflict, SOAS University of London.