The hidden value of museum objects: How we value objects

Behind the scenes of museum collections, valuation is a delicate balance of history, market forces, and meticulous research—uncover how museums assign worth to priceless artefacts beyond their monetary value.

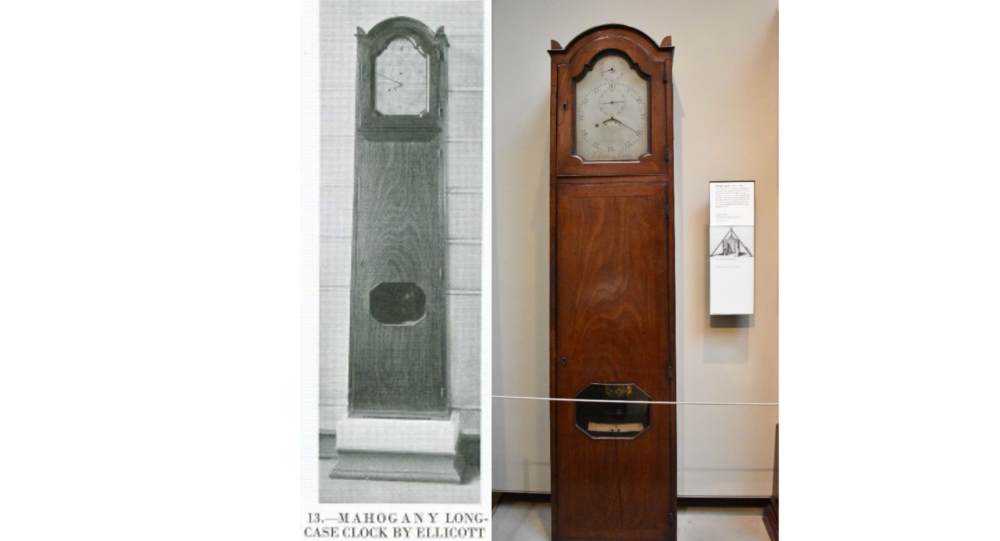

Wandering within the galleries of the British Museum, you might stumble upon a long case clock. However, upon closer inspection and a glance at the label, you may notice that the clock is on loan from the SOAS Gallery. Its origins date from the mid to late eighteenth century and was made by John Ellicott, one of the most distinguished clockmakers of the time. A clockmaker to George III and King Ferdinand VI of Spain, Ellicott’s portable observatory regulators were supplied to notable figures like Nevil Maskelyne, Charles Mason, and James Cook. Beyond its craftsmanship, Ellicott was also interested in astronomy, observing the Transit of Venus in 1761.

While museums acquire objects for their historical narratives, there are occasions when they must also assign a monetary value. This article explores how and why valuations are conducted within the museum sector.

The unseen work of valuations in museums

Valuation management is a crucial yet often invisible aspect of museum collections work. Museum staff are not authorised to provide valuations for public inquiries as they are not professional valuers. However, understanding valuation processes is essential for acquisitions, loans, insurance, conservation, and even potential losses or damages.

Several factors influence an object’s valuation. Consider a clock: if it was crafted by a prestigious maker, this might indicate a certain price. However, is that alone enough? The value may be shaped by connections to royalty, famous figures, or significant historical events. Rarity also plays a role—whether the clock is a one-off piece, part of a limited edition, or mass-produced.

We also must bear in mind that not all objects have an illustrious history, some are more commonplace, however, the value will lie in the item’s historical significance – its link to a particular person or event. The physical condition of an object can also affect its value, however, in all cases authenticity is key.

Managing expectations and establishing valuations

Valuations can raise questions and, at times, require managing expectations. Some lenders assume that the inclusion of their object in a museum display increases its market value. However, some artefacts have little commercial worth; their importance stems from cultural or educational significance rather than financial metrics. In such cases, determining value can be complex, sometimes resulting in merely a nominal figure.

Valuations are based on prevailing market conditions. While an object's exhibition history may enhance its prestige, it does not necessarily increase its monetary worth. When assessing an object's value, museums rely on documentation, provenance, and physical inspection.

The value of provenance is achieved through the bidding process. This is how the WOW factor of the sale of an item is then achieved, with the fight being to win the bid.

What is the market? How are estimates arrived at within auction houses? Usually, estimates consider the replacement value of an item. Provenance is important, but it is tricky to estimate how much provenance will affect the sale price until the hammer comes down on the day of any sale, as you may have two or more enthusiastic bidders trying to outbid each other. The value of provenance is achieved through the bidding process. This is how the WOW factor of the sale of an item is then achieved, with the fight being to win the bid.

Even with a great provenance, it may be difficult to value a rare and unique object, as these may never come up for sale on the open market, and so there is nothing to assist in attributing a fair market value. Fair market value also cannot anticipate future sales, and therefore, a valuation must be based on what a similar object might have achieved at auction at the time of the valuation. A valuation must be consistent with today’s market for a particular type of object.

Government Indemnity and the role of insurance

When loaning objects, museums may seek coverage through Government Indemnity, a scheme offering an alternative to commercial insurance. This process involves careful valuation: should the museum accept the lender’s proposed figure, or should independent assessments be pursued? Negotiations may arise when owners and museums disagree on valuation, requiring supporting evidence and expert input.

Government Indemnity Guidelines emphasise that valuations should ensure neither financial loss nor gain: “The party suffering the loss should not be out of pocket as a result of that loss, but neither should the loss provide them with an opportunity to profit thereby.” Auction estimates usually provide lower and upper limits, with the upper limit being the benchmark for insurance and indemnity purposes.

Making fair and informed valuations

As Collections staff, we work hard to ensure valuations are fair. We diligently research and provide a summary of how a valuation has been reached. We also confirm how a valuation reflects the market, providing comparisons and similar examples where they may be found. The thought process must be trackable. We must be careful not to under or overvalue, as incorrect valuations can lead to inadequate cover. As you can see, this work is paramount and crucial to all we do in bringing loans in, enabling loans out and in assessing acquisitions as heritage assets (I.e. an item acquired for its contribution to heritage and culture).

In many cases we do seek independent advice, however, our understanding of the provenance of the object enables the valuer to provide a more informed value, hence the importance of knowing your collection, and the histories behind each object, the stories that they tell.

In all cases, although the process is important, and the monetary value is relevant for several collection management functions, it should be noted that it is secondary to the object’s historical and cultural value or fit within a museum’s collection.

About the author

Maria Rollo is the Collections and Engagement Officer at the SOAS Gallery.