A history of Christmas pudding

Charting the dramatic history of the Christmas Pudding, from a medieval meat porridge starter to a Christmas revival from the Victorians and a tool and symbol of the British Empire.

From the chaos of the Christmas dinner kitchen, your nan appears, holding a ball of fire. The Christmas pudding has arrived. This pudding is certainly one of the most visually dramatic foods, but did you know it also has one of the most dramatic histories?

It began as a meat porridge starter, became sweet via colonial trade and received a Christmas revival from the Victorians to become a tool of the Empire. With key imported ingredients like sugar, spices and dried fruit, this article reveals how our national Christmas pudding might not be so British after all.

The medieval times were not-so-sweet

Life was harsh in medieval Europe, and so was the food. Meals were built around survival and not indulgence. Grain provided the bulk of calories, with poorer people consuming pottage (a thick soup). It was a variation of food called ‘Plum Pottage’, where any mix of meats, spices and dried fruits was cooked together, that laid the foundations for what we now know as the Christmas pudding.

Another earlier example comes from the royal kitchen. A recipe called ’Fygey’ was first uncovered in one of the oldest known English cookery books. Compiled in 1390 by the master cook of King Richard II, the recipe stated: “Take blanched almonds, grind them, and draw them up with water and wine. Add quartered figs and whole raisins. Add powdered ginger and clarified honey. Boil it well, salt it, and serve.”

Fygey sound familiar? The name survives today, not in the kitchen, but in a popular Christmas song. When carollers bellow out “Now bring us some figgy pudding” they are reminding us of the origin of the Christmas pudding we know today.

The evolution to a sweet, Empire-fueled pudding

In the 17th century, Brits moved away from the soupy stodge by wrapping the ingredients in a buttered and floured cloth, which was then boiled to create a more solid pudding. Even with this new form, the dish would not have been served as a dessert, but instead presented alongside the main or as a starter. This might be the last variation of a truly British Christmas pudding.

This sugar was produced on plantations, that depended on the forced labour of enslaved Africans. This reminds us of the troubling realities that underpin this pudding.

In the 18th century, it became sweet. The shift towards a sweet Christmas pudding was possible by Britain’s expanding access to Caribbean sugar. This sugar was produced on plantations that depended on the forced labour of enslaved Africans. This exploitation made sugar increasingly cheap and “widespread by the early 18th Century," noted historian Lizzie Collingham.

Historian Kaori O’Connor noted: 'The most English of dishes made from the most un-English of ingredients'.

"Now the [British] poor could afford sugar, or at least treacle, or molasses – the residue that remains when refining sugar." This reminds us of the troubling realities that underpin this pudding. If you’re interested in learning more about this subject, a good starting point is ‘Sweetness and Power’ by Sidney W. Mintz.

A national dish and imperial symbol

In the 19th century, the pudding became a symbol of the nation. Along with sugar, the other main pudding ingredient (spices and dried vine fruits) were also imported. Historian Kaori O’Connor noted: “The most English of dishes made from the most un-English of ingredients”. It’s certainly ironic, and the reliance on these trade routes led to the pudding representing Britain’s imperialism, trade and power.

The famous political cartoon by James Gillray’s, shown in Figure, 1 demonstrates this point. Titled ‘The plum pudding in danger’, the UK prime minister William Pitt and the younger Napoleon Bonaparte carve out the steamed pudding, shaped like earth itself. The pudding isn’t just a food, but a metaphor for power: Britain and France were literally carving up the world.

Victorian reinvention and festive ritual

We have Charles Dickens to partly thank for the festive evolution of the pudding. He turned it from a globe into a Christmas icon topped with holly and lit on fire. From his famous 1843 book ‘A Christmas Carol’, he writes: “With the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half a quartern of ignited brandy and bedlight with Christmas holly stuck into the top. Oh a wonderful pudding!”

The monarchy also reinforced this trend in Christmas pudding. Three years after Dickens’ account, Queen Victoria’s chief cook ‘Charles Elme Francatelli’ publishes his recipe book ‘The Modern Cook’ which features a suitably royal recipe for plum pudding. If the royals enjoyed plum pudding at Christmas, so will the public!

The pudding became so popular that the last Sunday before Advent became known as “Stir-Up Sunday”, the day when Christmas pudding should be made. The whole family comes together to make and stir the Christmas pudding, and it has become customary to drop small silver charms and coins into the pudding. If you found one in your slice on Christmas Day, it would bring you fortune for the year ahead.

From the 20th century to now: War, Empire and reinvention

The power of the pudding continued to be ignited into the 20th century, but world wars and changing politics reshaped it once again. During World War 1, ingredients such as dried fruit and spices were rationed, leading to smaller, simpler puddings.

For the soldiers, the pudding was a source of camaraderie and nostalgia while on the battlefield. Fundraisers were set up to send puddings, and on December 24, 1915, it was reported that three million pounds of Christmas puddings were to be delivered to soldiers to enjoy.

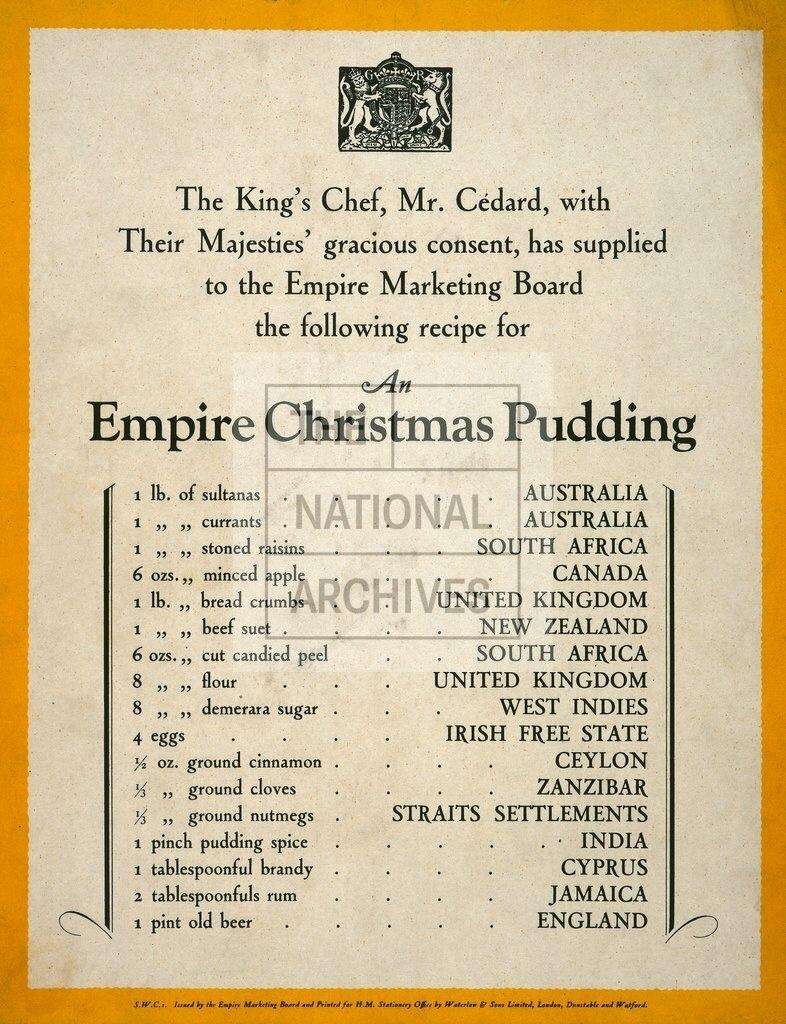

Later on in the century, when the Royal Family were trying to strengthen cultural ties across the British Empire, King George V and Queen Mary announced that their Christmas Dinner would consist entirely of foods produced within the Empire. The Empire Marketing Board ran a marketing campaign where a schoolboy made the King’s Christmas pudding. The ‘Empire Christmas Pudding’ was born (see Figure 4). This helped cement the pudding as a national and imperial symbol during the interwar years.

The Empire Christmas Pudding...helped cement the pudding as a national and imperial symbol during the interwar years.

In 2022, we were reminded once more of the heritage of the Christmas pudding when a major British supermarket centred its festive advert on the dessert, celebrating its royal connection and national symbolism. The empire may have waned, but the representation of the British pudding remains resilient and continues to be a cherished part of Christmas today.

Header image: Sean Ferigan via Unsplash.

About the author

Pamilla is an MA Global Journalism Student at the University of SOAS. She is studying remotely while travelling Central and South America, hoping to use these new experiences to shape her research and blog articles.