Uncovering Shan Manuscripts at SOAS Library

Jotika Khur-Yearn, Southeast Asia Librarian at SOAS, discusses his recent work on a project to improve catalogue metadata for the library’s important collection of Southeast Asian manuscripts, bringing these to light for international research.

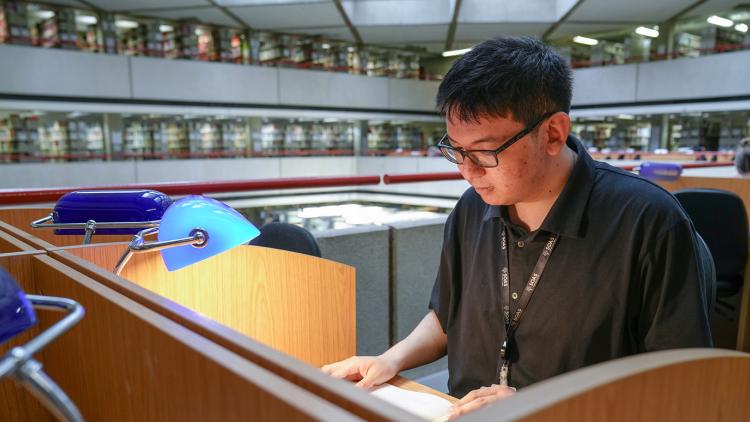

As part of the Manuscript Metadata Project being run by our Special Collections team, I was given an opportunity to use my linguistic skills to work with the Southeast Asian manuscripts made from traditional paper (excluding palm leaf and other formats), identifying scripts and working with regional scholars and experts.

I was tasked with enriching existing catalogue records with detailed information on the extent, physical characteristics and provenance of items, as well as providing bibliographies where appropriate, and ensuring that the enhanced catalogue records are accessible and user-friendly for researchers, students, and the wider public.

Of the 79 paper manuscripts catalogued by the project, 53 are manuscripts originally from Shan State and its borderlands, while the remaining 26 items are Burmese and Thai manuscripts. The Shan borderland areas referred to here are the prefectures in Yunnan in China bordering with Myanmar, Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Mae Hong Son in northern Thailand, Kayah State in the south, Hkamti/Khamti of Sagaing Division in the west, and Kachin State in the north-west, where some of the SOAS Shan manuscripts originated.

All manuscripts are kept in archival storage, with controlled temperature and humidity, and despite their old age, most are still in good condition. The good news is that SOAS Library now has a professional Conservator who can advise on the care of old documents to ensure their long-term preservation.

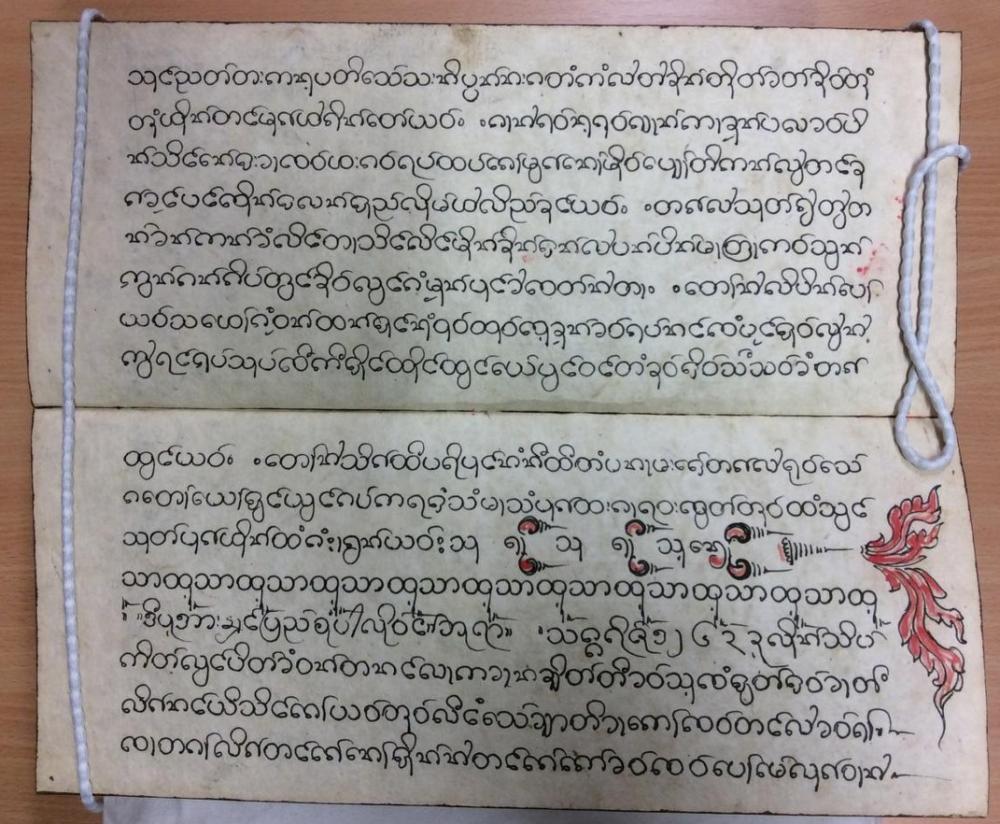

There are two main types or forms of Shan paper manuscripts, namely, rolled manuscripts, pap ken, (Fig. 1) and concertina-style folded manuscripts, pap top, (Fig. 2) also known as Parabaik. While both types of manuscript exist side by side, the former is thought to have existed since ancient times, and the latter was introduced at a later date but became more popular, notably due to their beautifully gilded covers with glorious designs of floral artwork and gem-like shiny glass-cuts (Igunma 2016).

There is one of such notable folded Shan manuscript in the SOAS collections, titled “Nang Yi Hseng Kaw” (MS 46802) and dated 1901; it is one of the manuscripts selected for the SOAS exhibition on the Arts of Southeast Asia from SOAS Collections (May 2014 - September 2016), held in in the Foyle Special Collections Gallery of the SOAS Gallery (Yahya 2017). On the other hand, the rolled Shan manuscripts also have their own unique and significant designs, and many are wrapped in beautiful textile cloths to protect the papers within (Ingunma 2022).

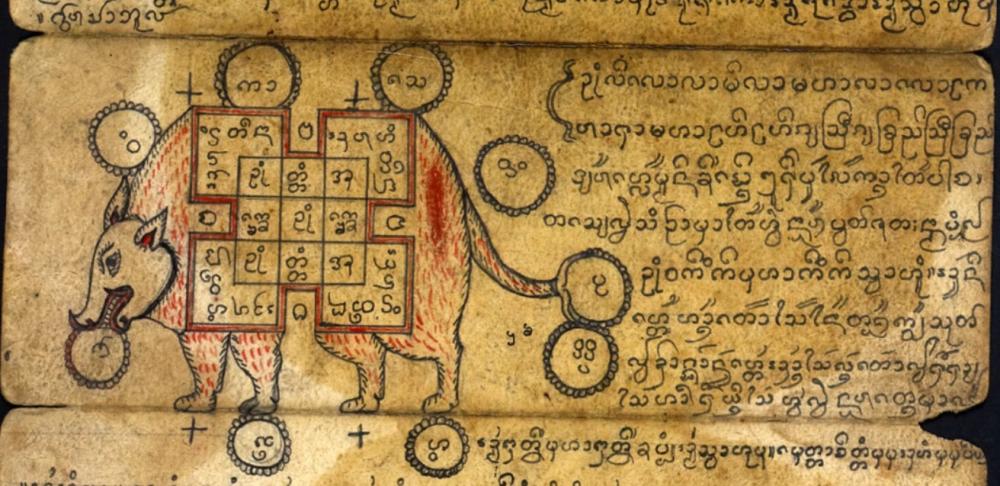

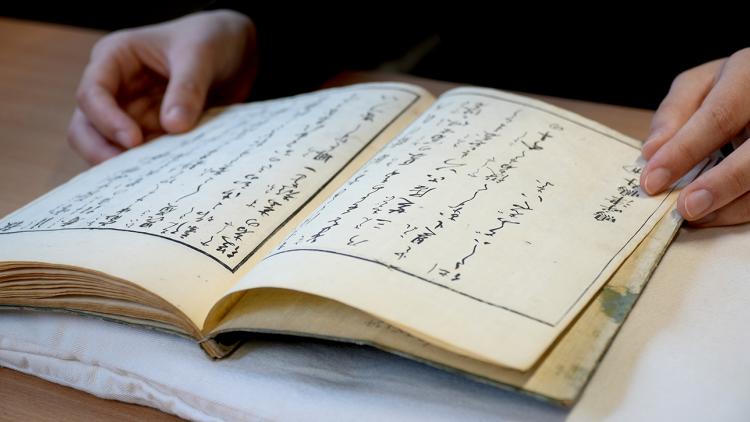

Setting the forms and covers aside, the Shan manuscripts are arguably treasure houses containing invaluable sources of information on various subjects. While the majority are on Buddhism, they cover other core subjects, such as history, cultures, arts, calligraphical writing (Fig. 3) and astrology as well as unique topics such as traditional medicine, healing, charms, tattooing (Fig. 4) and folk stories.

Some of the Buddhist texts have several editions and have been copied numerous times (Khur-Yearn 2009). In addition to the main texts, many Shan Buddhist manuscripts have long colophons giving details of their original sponsors as well as donors, including the dates of the manuscripts and names of places. There are a few such Shan manuscripts in the SOAS collections, which have extensive colophons detailing when and where the manuscripts were produced as well as the names of people involved, including the author and sponsors of the manuscripts.

It is also worth noting the existence of handwritten papers (MS 50109 and inside the box of MS 46802) giving detailed descriptions and notes on some of the Shan manuscripts in the SOAS collections. These belonged to a former colonial officer for British Burma and the Shan states, Captain H. J. Inman, who, likely after retirement from his colonial work, became a Shan language teacher at SOAS between the 1930s and 1940s. It was during this period that he undertook in depth reading of the Shan manuscripts and through his extensive notes left behind a legacy for researchers on his career and works in connection with the Shan people, language, culture and literature.

In short, through the project, we have aimed to enrich catalogue records for these manuscripts to enhance discoverability, and hope that with the advancement of information technologies for library and archival systems, there will be automated search tools to support researchers find the treasures recorded in these hundreds of years old manuscripts housed in the SOAS Special Collections.

If you're interested, here is some further reading:

- Jana Igunma wrote a post in 2016 for the British Library’s Asian and African Studies blog called “A Bar of Pure Gold: Shan Buddhist Manuscripts.”

- In 2022, she contributed another piece to the same blog, “Manuscript Textiles in Southeast Asian Collections.”

- Kam Mong published a book in 2012 titled Shan Thammasat Manuscripts (Tokyo: Mekong Publishing Company).

- Jotika Khur-Yearn explored seven Shan versions of the Satipatthana Sutta in his 2009 article “Richness of Buddhist Texts in Shan Manuscripts,” which appeared in the journal Contemporary Buddhism (Vol. 10, Issue 1, pp. 85–90). https://doi.org/10.1080/14639940902968954

- B. J. Terwiel and Chāichư̄n Khamdǣngyō̜ttai co-authored the 2003 book Shan Manuscripts (Stuttgart: F. Steiner).

- The Arts of Southeast Asia from the SOAS Collections (edited by Farouk Yahya, 2017, Penang: Areca Books) is another useful reference.

For more information about the Shan manuscripts or any enquiries about SOAS Special Collections, please contact us at special.collections@soas.ac.uk.