“You make me do too much labour”: What Paris Paloma’s anthem reveals about care, capitalism and gender

Paris Paloma’s viral hit Labour is more than a feminist anthem. Dr Sophie Chamas explores how it reveals a window onto the hidden, gendered and racialised work of care that capitalism depends on but refuses to name or pay.

I can’t recall exactly when I first heard Scottish singer-songwriter Paris Paloma’s hit single “Labour” (2023). If memory serves, before I’d heard of Paloma themselves and listened to the song purposively, properly, and in its entirety, I’d found myself regularly and unwittingly encountering – to the point of vexation – its melody and snippets of its lyrics as I scrolled absent-mindedly through social media. I eventually relented and looked up the source, engaging with it relatively superficially and attributing the song’s ubiquity to its catchy melody and chorus.

The lyrics behind the viral song

One day, as I was walking to the Overground and listening to music on shuffle, I came upon the song yet again. This time, I listened intently to the lyrics: “All day, every day, therapist, mother, maid. Nymph, then a virgin, nurse, then a servant. Just an appendage, live to attend him so that he never lifts a finger. 24/7 baby machine, so he can live out his picket-fence dreams. It’s not an act of love if you make her. You make me do too much labour.”

Ah, I thought. This was a feminist anthem – a decrial of women’s needs and wants being subordinated to that of men within what are meant to be romantic partnerships – hence, the popularity. I returned to social media in search of the many videos that the song was sutured onto, and which I had previously scrolled past inattentively.

I found reel after reel of women commenting on gendered inequality or violence, using the song and its defiant tone to evince a posture of recalcitrance in the face of oppressive norms of feminist comportment and the normalisation or justification of household abuse. Of course, the song is popular, I thought. It names something that most women have, to some degree and in some form or another, had to contend with because of their social positioning as women.

Of course the song is popular, I thought. It names something that most women have, to some degree and in some form or another, had to contend with because of their social positioning as women.

What excited me about the song, however, was the use of the word “labour” throughout the lyrics. Popular culture is peppered with tales of abusive relationships within which women find themselves trapped, and of the gendered burdens they are made to bear. Care continues to be problematically perceived and approached as a gendered trait, as the ‘domain’ of women, as something that comes naturally to them and that they should therefore attend to.

Care, however, is learned and practiced, not inherited or biologically available – it involves labour. It is not an organic product flowing freely and easily from women, but an affective experience composed of a series of arduous, regularised, and invisible tasks. Feeling and being cared for isn’t something that just happens to us, but is the result of a deeply gendered form of work that takes place around us all the time, and which we routinely fail to acknowledge, appreciate and, crucially, remunerate.

What the song tells us about invisibilised gendered labour

This song, I thought, is exposing the process that Marxist feminists call social reproduction to the masses – sort of. The song charts the what of invisibilised gendered labour, but it falls short of telling its audience the why. What if one were to direct the righteous rage that the song inspired in so many women towards a systemic rather than individual target? Is the problem simply the abusive or entitled man at home? Why does society reinforce this type of gendered behaviour? Why are women made to “do too much labour?”

What if one were to direct the righteous rage that the song inspired in so many women towards a systemic rather than individual target?

A song, of course, is not a political manifesto, but it is important, when we think about the gendered labour of the home and the abuses that extend from its obscuration, that we engage with why this labour is needed and why it needs to be gendered – and by extension obscured – in the first place.The answer, Marxist feminists tell us, lies with capitalism and its workings. Capitalism relies on the worker to generate surplus value, but who generates the worker? Who nourishes the worker, and tends to the capacity to return to the workplace?

Historically, it has been the unwaged labour of the household, to which women have been traditionally designated, that sustained the male worker and enabled him to produce surplus value for capitalist society. Capitalism has relied on this labour, and relied on it being unwaged, to avoid having to provide workers with more of the means for sustaining themselves, which could have a negative impact on profit margins. Capitalism, then, relies on the labour that Paloma decries in her song (amongst other social relations that are beyond the scope of this blog post to examine).

Even though women have long since entered the work force, the work of social reproduction in the heterosexual home continues to fall to them.

Even though women have long since entered the work force, the work of social reproduction in the heterosexual home continues to fall to them, with domestic responsibilities alongside child rearing still overwhelmingly being tackled by women. Think, for example, of the disparity between paternity and maternity leave in most contexts.

Many women now bear the burden of both wage labour to enable themselves and their families to survive in a world where living costs continue to increase, while also continuing to engage in the uncompensated and, more often than not, unappreciated work of creating and tending to infrastructures of care that sustain family units and kin networks.

Tradwife and profit accumulation

This is why Paris Paloma’s “Labour” provides a useful lens through which to critique the concerning “tradwife” digital subculture. Short for “traditional wife”, the “tradwife” phenomenon refers to women who have made a name (and, in many cases, a profitable business) for themselves online promoting a ‘traditional’ lifestyle and gender roles.

Some of the more extreme and pious of these women expound the benefits of ‘submitting’ to one’s husband, but many of them take a more subtle, less dogmatic and religious approach, focused on the joys of cooking from scratch for their husbands and children and tending to the home more generally, and the peace and pleasure they derive from a life of domestic bliss.

What these women – dressed in retro-feminine dresses in which it is hard to imagine making elaborate meals – neglect to tell their audiences is that the domestic serves as a vehicle for profit accumulation for them, making millions of dollars (many of these women are US-based) off of brand deals or selling their ‘from scratch’ ware.

What they also neglect to tell their audiences is that to have the luxury of making chewing gum from scratch, or better yet, the chocolate for chocolate chip cookies, one has to be free of the burden of, you know, surviving financially in a hostile world. The wealthy don’t need to work – either as wage labourers or in the arena of unwaged housework. The bills are paid, and the toilets are clean – they can put on a polka-dotted dress and get started on that heritage grain sourdough and homemade raw milk butter.

Capitalism depends on cycles of exploitation

The problem with the relatability of a song like “Labour”, however, is that it masks over the fact that a lot of what we consider the gendered work of the home has long been carried out by migrant, racialised, and working-class women, at least in the West (but also elsewhere, in the Middle East, for example).

The problem with the relatability of a song like “Labour”, however, is that it masks over the fact that a lot of what we consider the gendered work of the home has long been carried out by migrant, racialised, and working-class women.

While feminists in the West celebrate their historic achievements in terms of women’s rights, and take pride in women’s presence in the workforce, they neglect to mention that many of these rights, particularly those related to labour, have been enabled by the outsourcing of ‘women’s work’ to underpaid and exploited migrant, racialised, and working class women (and also men in some cases).

“You make me do so much labour” can be addressed to a man, but it can also be addressed to a woman who, instead of challenging the way gendered social reproductive work is perceived and approached, displaces it onto another, more vulnerable person, perpetuating one of the cycles of exploitation on which capitalism depends.

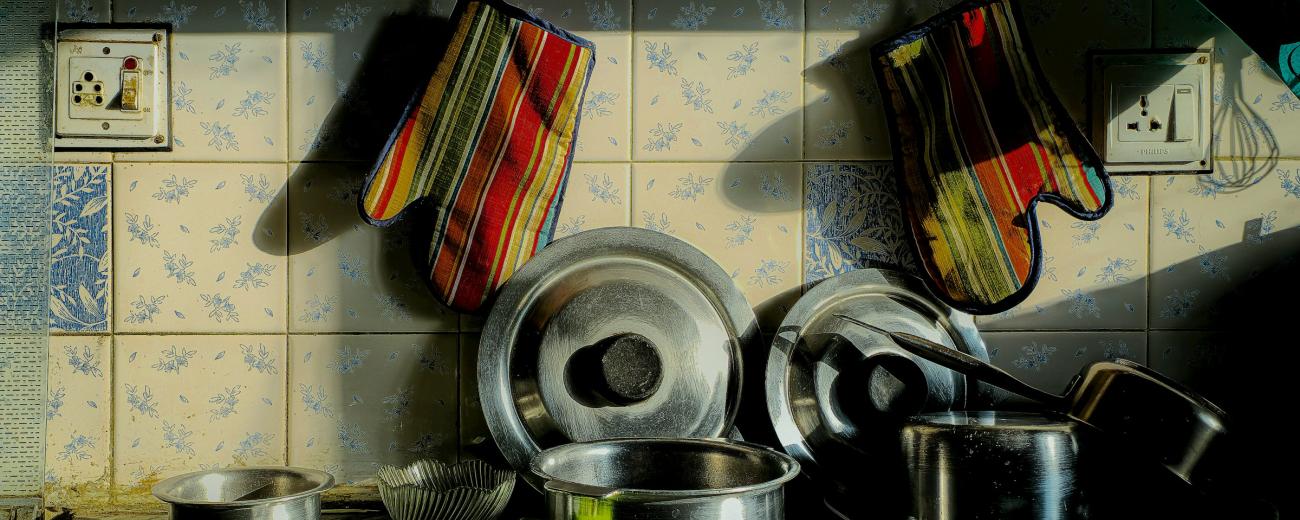

Header image credit: Mohammad O Siddiqui via Unsplash.

About the author

Dr Sophie Chamas is a Senior Lecturer in Gender Studies at SOAS University of London.