One more time: Anthropology, cinema, futures

The project regards anthropology and cinema as distinct yet related forms of culture critique; by revisiting the films of Théo Angelopoulos, it poses the question of how the real is fashioned in such films, charting the effects its cinematic reconstruction has been having on audiences.

Overview

Théo Angelopoulos’ (1935-2012) cinema is profoundly political, singlehandedly dedicated to filming the margins, those excluded, the migrants and refugees populating Europe’s south east. The screen is inhabited by Greek communist exiles returning to an unrecognisable ‘homeland’, village orphans en route to Germany in search of their father, dying poets, itinerant actors, people fleeing poverty in Albania, repression in Kurdistan. Rather than casting such margins in negative light, as desolate and in need, the films adopt an alternative valuation: in life at the margins they encounter a unique potential which when affirmed, it becomes fundamental in ushering us all in a future otherwise.

In his films alterity intersects with time: one of their distinctive features is that time rarely flows in linear, chronological, sequential manner. Like other directors such as Alain Resnais and Orson Welles, Angelopoulos equips the camera with the wondrous capacity to un-discipline time, allowing it to move in ‘dis-orderly’ fashion, capable of charging, often at great speed, backwards and then forewords. The result of such time-shifts is the eluding of the present as normative, stable point of reference, putting identity and truth into crisis: everything that unfolds on screen is part of a gigantic artistic and intellectual commitment to foreground becoming, keeping time always open so that time can be endlessly renewed on a constant basis, with each and every turn of events. While the means through which this is achieved rely on an innovative refashioning of long continuous takes, the becoming cinema announces holds immense anthropological value. In making description unfold temporally, it recommences critique on an immanent/anarchic basis, thus avoiding all forms of transcendence that instead mean to secure it against future perspectives emerging.

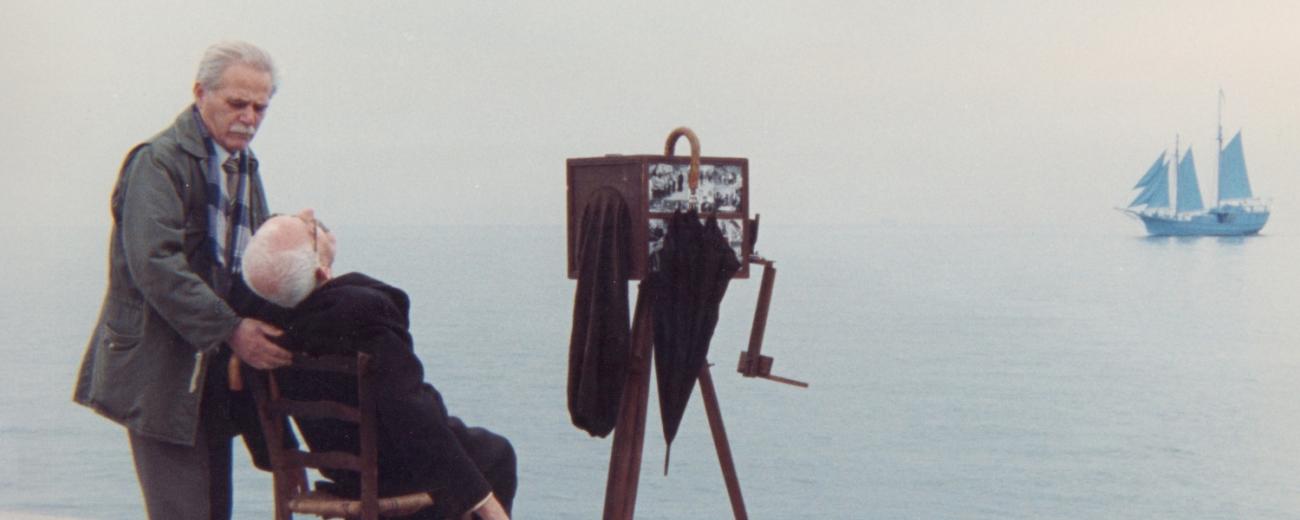

All of 13 feature films completed during an accolade-laden career spanning five decades reconstruct both poetically and carefully the realities of south-eastern Europe throughout the 20th century, paying attention to historical and ethnographic specificities. The coming together of cinematic mastery and anthropological sensibility is partly rooted in the director’s student days when, in the early 1960s, he attended lectures at The Sorbonne by Claude Lévi-Strauss and enrolled in Jean Rouch’s ethnographic filmmaking classes at The Museum of Mankind. Such confluence reaches an apogee when it serves as the foundation of his 1995 film, Ulysses’ Gaze: the film’s protagonist turns so obsessed with the ethnographic gaze of Yanaki and Milton Manaki, two Aromanian photography and cinema pioneers from the dying days of the Ottoman empire, that he becomes-Yanaki twice on screen while crossing spatial borders, journeying into different countries, and breaching temporal boundaries, moving in and out of the repeated making and unmaking of nation-states in the Balkans at the beginning and the end of the 20th century.

Image Credit

Still image from Ulysees' Gaze (1995)