Painting through a colonial lens: How British prints shaped how Southern India was imagined

An MA student, Himantika Mann, looks at three prints of Southern India by British artists and asks: what do they show, what do they leave out, and what can they still teach us about art, empire, and the politics of seeing?

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as the British Empire expanded across South India, artists like Thomas and William Daniell and Henry Salt travelled in its wake. They sketched temples, forts, and landscapes that were later transformed into aquatints and engravings for British audiences eager for scenes of distant grandeur. These images - now held in the SOAS collections - shaped how India was imagined: monumental, spiritual, and timeless.

Their work belonged to the Picturesque movement, a style popularised by figures like William Gilpin, which favoured dramatic ruins, irregular forms, and romantic decay, shown in Gilpin's Observations on the River Wye. Yet these prints were not neutral documents.

They reflect the selective gaze of empire: architecture is emphasised, ritual life is removed, and conflict is quietly left outside the frame.

They were made possible by British military victories - Tipu Sultan’s defeat had only recently opened these regions to European travellers, and they reflect the selective gaze of empire: architecture is emphasised, ritual life is removed, and conflict is quietly left outside the frame.

As an Indian student studying at SOAS - a university founded in 1916 to train colonial administrators - I now encounter these images from a different position. Once displayed in imperial drawing rooms, today they rest silently in archival drawers, seen by students and scholars who question rather than affirm their vision. That shift is part of the story.

Framed and reframed: A closer look at the prints

This post looks closely at three prints of Southern India - two by the Daniells, one by Salt - and asks: what do they show, what do they leave out, and what can they still teach us about art, empire, and the politics of seeing.

These prints do not merely reflect what was there; they shape what their audiences believed India to be.

To understand how artists like Salt and the Daniells constructed imperial visions of India, we must look closely at the edges of the frame, the choices of inclusion and omission, and the shifts between what was drawn, engraved, and published. These prints do not merely reflect what was there; they shape what their audiences believed India to be.

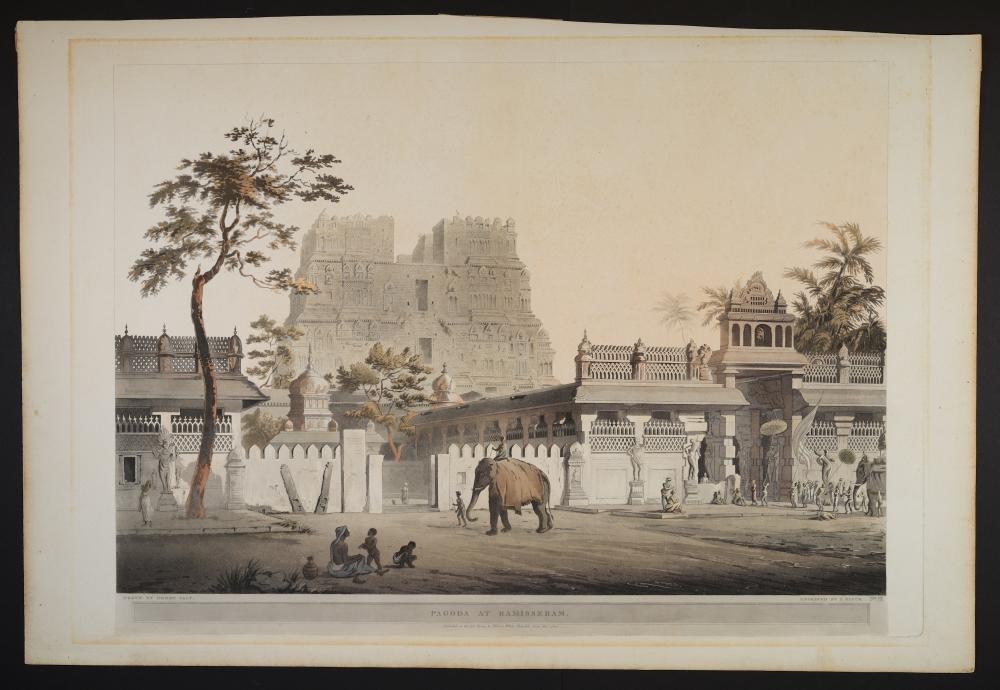

Picture 1: The Pagoda at Ramisseram by Henry Salt

Salt’s engraving of the Pagoda at Ramisseram (known present-day as Rameswaram), published in 1809, offers a carefully balanced view of the towering east gopura and surrounding structure. The perspective is frontal and architectural: wide foreground, scattered human figures, and the looming temple gate, dark and incomplete.

What’s striking is what doesn’t appear. The monumental gopura is clearly present but unfinished, confirmed by recent scholarship, which notes that the superstructure of the east gate was not completed until between 1897 and 1904 (Crispin Branfoot and Lennart Bes, “From All Quarters of the Indian World: The Temple at Rameshvaram, Hindu Kings, and Dutch Merchants,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society - forthcoming).

Salt’s drawing from 1804 captures this transitional state, a moment when the sacred architecture had not yet achieved the towering form familiar today. But instead of marking incompletion, the image abstracts it - suggesting grandeur without full clarity.

What remains is...a composition suited to the British taste for the exotic, but not its complexity.

Even more revealing is a comparison between the published aquatint and Salt’s original watercolour, which I examined at the British Library. The watercolour contains additional figures, a statue beneath a canopy in the left foreground, and a richer detail of jali screens—all absent in the final print. These elements lend texture to the scene: a glimpse of the temple as a living, inhabited space. Their removal in the engraving sharpens the architectural drama but erases the life of the site.

The temple at Rameshvaram was, and remains, a site of extraordinary religious importance - its long corridors lined with life-sized sculptures of donors, kings, and attendants from the 17th and 18th centuries. Early visitors remarked on these figures: painted, garlanded, and sometimes honoured by name.

Yet none of them appear in Salt’s published print. The framing privileges structure over story, monument over memory. What remains is a print that monumentalises the sacred while muting its cultural specificity - a composition suited to the British taste for the exotic, but not its complexity.

Picture 2: The Great Bull at Tanjore by Thomas and William Daniell

This print from the Oriental Scenery series offers a frontal view of the great Nandi bull at the Brihadisvara temple in Tanjore. The sculpture - a sacred mount of Shiva - dominates the image, framed by evenly spaced pillars and a deep sense of recession.

But the composition, while architecturally pleasing, is visually manipulated. Lord Valentia, who visited the temple in 1804, noted that the Daniells had exaggerated the spacing of the pillars to better reveal the bull (Archer, Early Views of India). Though the number of columns is correct, the intervals have been artificially widened, altering the real spatial rhythm of the temple.

What might have been an active site of daily religious practice is rendered as an object of serene admiration - India reimagined as architecture.

In doing so, the Daniells turn Nandi from a devotional object to a spectacle. The scale is magnified, and the context is abstracted. The spiritual atmosphere of the temple is flattened into formal harmony. No worshippers appear. No rituals are suggested. What might have been an active site of daily religious practice is rendered as an object of serene admiration - India reimagined as architecture.

Picture 3: Verapadroog in the Barramahal by Thomas & William Daniell

In contrast to the monumental calm of Tanjore, this print offers a Romantic landscape: the rugged hill-fort of Verapadroog, cloaked in vegetation, perched above dense jungle. The scene is dramatic, but still - there are no signs of conflict, occupation, or movement.

Yet history tells a different story. The Barramahal hills had only recently been ceded to the British after Tipu Sultan’s defeat in the 1792 treaty. The Daniells’ own journals mention passing through five defensive gates and encountering a local officer collecting the grain - a sign of recent military action. The fort itself was still associated with Tipu’s resistance, and the jungle below teemed, as one of the Daniells wrote, with "tygers" and danger.

None of this makes it into the print. Instead, Verapadroog becomes a picturesque ruin, folded into the aesthetic lexicon of the sublime. The fort is framed not as a political site, but as a visual one - a perfect mountain perch for the British eye.

The landscape is not simply recorded - it is reordered, aestheticised, and depoliticised.

Together, these three prints offer more than artistic variation. They reveal a pattern of transformation: from encounter to composition, from event to image. The landscape is not simply recorded - it is reordered, aestheticised, and depoliticised. India, as seen through these prints, becomes legible to the empire - but not to itself.

Looking again: From archive to afterlife

Today, these prints lie quietly in drawers at SOAS. Once, they helped train colonial administrators to see India as timeless, grand, and knowable. Now, they invite different questions: What do they reveal? What do they erase?

As an Indian student researching these images in the former imperial centre, I encounter them with a double awareness. They are both artworks and artefacts of power: images that flattened living landscapes into picturesque scenes fit for British eyes.

The choices Salt and the Daniells made - what to include, what to omit - were not neutral. They turned temples into architectural studies, sacred sculptures into spectacles, and sites of recent conquest into tranquil ruins.

The choices Salt and the Daniells made - what to include, what to omit - were not neutral. They turned temples into architectural studies, sacred sculptures into spectacles, and sites of recent conquest into tranquil ruins.

That these prints are now kept in the SOAS Gallery’s storage - once hung around the university and now shown on a rotating basis in the Foyle Gallery - is part of their story, and mine too. SOAS, once founded to train colonial officers, has become a place for rethinking what such images meant and what they still mean. The act of looking again becomes a form of critique: not rejecting these prints but reading them against their grain.

To study them now is to see both what they showed and what they refused to see - and, perhaps, to imagine what new stories they might help us tell.

The three prints currently on display in the Foyle Gallery are in the dedicated space for the SOAS Permanent Collections on the ground floor of the SOAS Gallery.

About the author

Himantika Mann studies MA Curating Cultures at SOAS University of London.