All pain, no gain: The gender story of Korean economic development

One of the famous movies about South Korea’s economic development is Ode to My Father (2014). This movie describes South Korean economic development from the Korean War to the present time from the point of view of ordinary man Deok-soo, depicting how hard he worked and what he sacrificed for his family as a first son and father. The movie highlights and appreciates people’s strenuous effort in Korea’s economic development. In this movie, however, there is no story about his wife, Young-ja, who was also responsible for her household as a first daughter and mother.

South Korea’s economic development is one of the most notable successes among developing countries. The GDP per capita in South Korea was 1.6 trillion Dollars in 2020, which is 400 times larger than its GDP in the 1960. However, scratching beyond the surface of the success story, we can see that there is a pervasive undervaluation of women’s work, as in the case of Young-ja. To take a closer look into this hidden aspect, it is necessary to use other lenses besides evaluating economic development using GDP growth. Getting away from the existing evaluation of Korean economic development, this post will use feminist economic concepts to question the success story of Korea and its future.

Feminist economic theory challenges established approaches focused on the production and market-based analysis in economic development. Feminist approaches expanded the notion of development to include social reproduction, emphasizing the value of reproductive work done by women but not appreciated in the market economy. In other words, the feminist approach sheds light on the role of women in development, providing a chance to look closely at women’s undervalued work.

Undervalued women’s role in economic development

Korean economic development results from the hardworking of all the population, but Korean women have been described as a minor character in the grand success story. Since the 1970s, women have played a crucial role in supporting their household by working in ‘nimble fingers’ industries, that is, labour-intensive and export-oriented industries. In 1983, four-fifths of working women were informally employed in light manufacturing factories. Having been paid only 46.8% of their male counterparts, women’s cheap labour enabled Korea to be competitive in the world market. Despite their low wage, Korean young women contributed an important source of income to their household, and 12% of them saved their wages for their brother’s education.

However, women’s labour is not appreciated enough in Korea. First, despite educational equality, there is a significant gender pay gap in Korea, which has been the widest among OECD countries for a couple of years. The significant gender pay gap conflicts with the human capital theory that attributes the wage gap to human capital differentials.

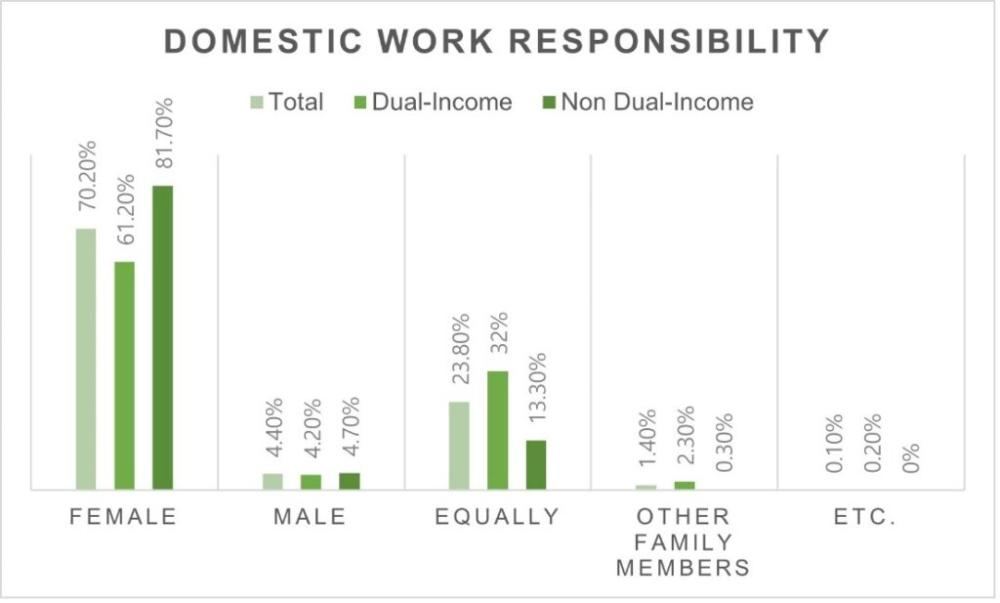

Second, the human and social reproduction burden on Korean women is considerable. Still, domestic work and care work are considered the responsibility of women. Korean women and men’s domestic work participation (Figure 1) shows that Korean women are extensively more responsible for domestic work, and dual-income households are not an exception. In addition, during the Covid-19 pandemic, 95% of women of 30-45 years old who quit their job were married women, indicating that women were more responsible for childcare.

The experience of gendered discrimination led to changes in young women’s behaviour in South Korea, such as the 4B movement. The 4B (4Nos) is a feminist movement supported by many young feminists who reject patriarchal relations by refusing heterosexual marriage, childbirth, romance and sexual acts. 54.7% of unmarried Korean women answered that they will not get married, which is 13.5% higher than their male counterparts. In addition, the birth rate in South Korea is getting lower, recording 0.92 in 2019, which is the lowest among OECD member countries.

Gender equality: The right and the smart thing to do

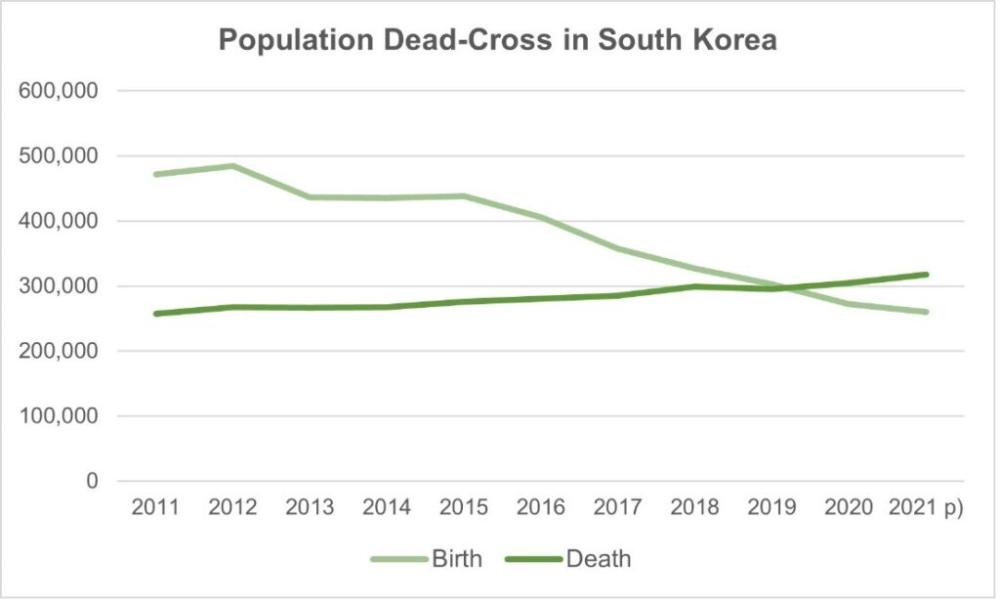

Already experiencing a population dead-cross, meaning that the number of deaths has surpassed the number of births, South Korea’s population is decreasing with the decline of the working-age population (Figure 2). Consequently, there will be less tax revenue, with more tax expenditure on welfare such as health care, caused by the ageing society. The question is, how can the Korean government wisely manage this situation and promote sustainable economic development? In this situation, gender equality is the right and the smart thing to do.

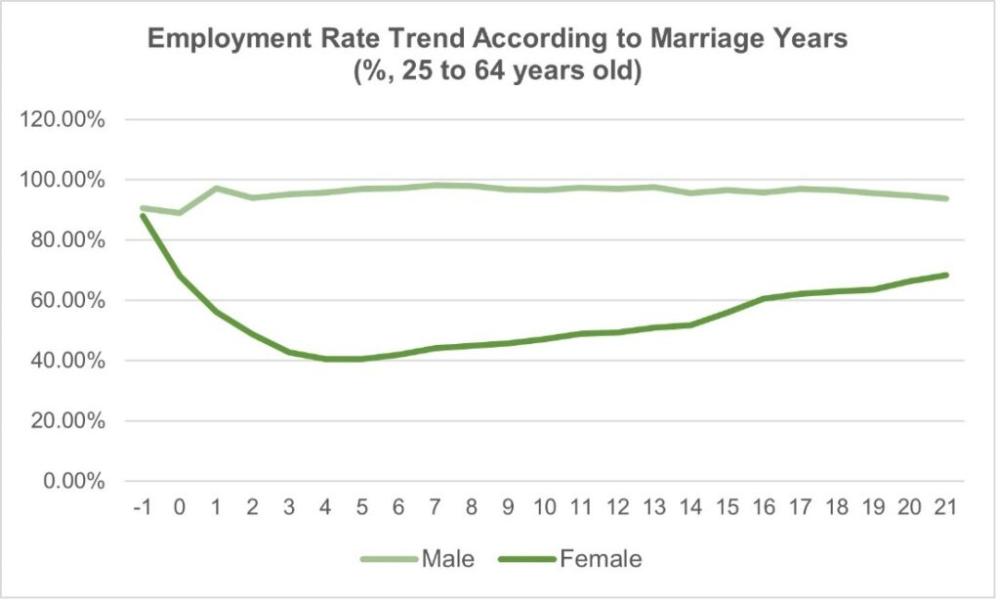

Studies show that gender equality is helpful in economic growth by increasing labour market productivity and optimal use of human resources. South Korea is already equipped with a highly educated labour force whose employment rate is only 53%. This employment rate tends to decline when the woman marries (Figure 3) and gives birth due to the difficulty of reemployment. (Yoo, 2021) Consequently, the fear of a career break leads to a low birth rate. Therefore, eradicating obstacles of gender discrimination in the workplace, the difficulty of reemployment, and the double burden against women can help the sustainable development of the Korean economy.

In conclusion, through the lens of feminist economic theories, the development of the Korean economy is just half-successful. Thus, the Korean government should account for gender in its policy proposals for sustainable economic development post-Covid era. Furthermore, scholarship should reevaluate South Korea’s success story beyond national income bases.

About the Author

YuJeong Hwang is an MSc Political Economy of Development student at SOAS. Her research interests include gender economics, economic policies during the crisis, and economic integration in the Asian Pacific Region.