Are universal pension systems a way to acknowledge women’s unpaid and undervalued work?

The indispensable contribution women make to society continues to be unseen

Social protection schemes cannot succeed unless they recognise all contributions to society. While it is widely acknowledged that access to pensions can reduce old-age poverty, the most common state pension scheme, funded by payroll taxes, is inherently gender-biased. The main objectives of pensions are to provide stable incomes, smooth consumption over an individual’s lifetime, and reduce old-age poverty. Pension schemes fulfil these intentions for those who have contributed enough savings throughout their working life but often leave individuals who have not ‘formally’ met the requirements behind.

The gap in opportunities for accumulating pension benefits begins much earlier in life. The overwhelming societal focus on economic growth devalues work performed outside of the market setting. Failing to recognise the contribution of unpaid reproductive work, predominantly undertaken by women, puts a large segment of the population at a disadvantage. The monetary value of unpaid care work for women aged 15 and over is huge; by disregarding its value, $10.8 trillion is excluded from the size of the global economy every year. Standard statistics ignore the provision of unpaid services, and policies rarely acknowledge that women are foregoing opportunities to earn and save for later in life while they are providing services that should be supplied by the state.

Feminist economics, the branch of economics that uses insights from feminist theory to improve economic thinking, is vital to policy making. Economic inequality is built upon numerous intersecting societal disparities, including gender, race, and caste; most individuals at the lower end of the economic pyramid are women. It challenges the focus of mainstream economics, which is predominantly centred around wage labour and ignores the societal and economic value of unpaid work. By bringing gender to the forefront of economic analysis, feminist economics highlights structural inequalities that need to be considered in policy making. Excluding gender insights leads to the creation of gender-biased social security policies, which widen inequality and poverty.

Mainstream economics does not recognise that globally, women and girls are more likely to be employed in low-paid, undervalued, precarious jobs. Female workers represent a high percentage of all informal, underpaid, and unpaid work. Oxfam calculates that more than 75% of unpaid care is carried out by women and unpaid caring responsibilities result in 42% of working-aged women being excluded from the paid labour force, which leads to their societal contributions being unaccounted for.

Gender social protection gaps are apparent through disparities in pension entitlements

Disregarding the positive impact reproductive roles have on the economy leaves women continuously disadvantaged; a high proportion of ‘invisible work’ leads to fewer completed hours of formal work and fewer years of insured employment. When these dynamics are not considered, policies that can appear to be gender neutral are often marked with male bias. In the case of retirement policies, policies based on formal employment contributions drive lasting gender divides in old age social protection.

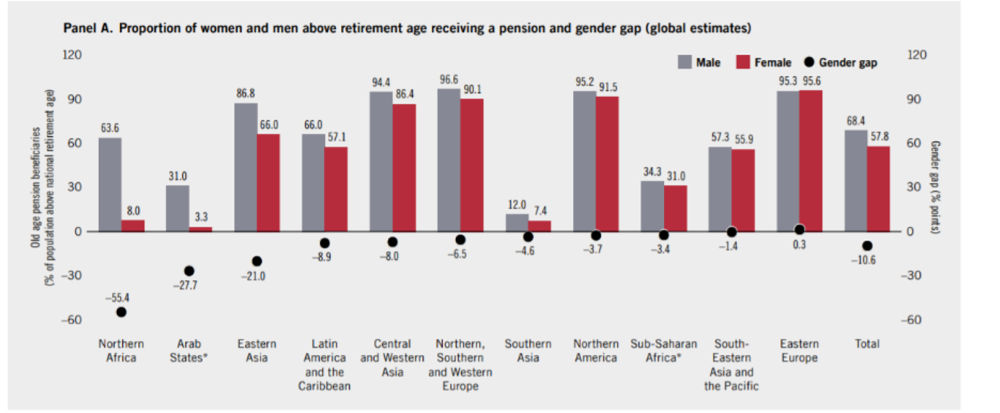

Figure 1 highlights the gender gap in pension beneficiaries by region. On average, the proportion of women receiving a pension is 10.6 percentage points lower than men. The largest differences can be seen in Northern Africa (55.4 percentage points), the Arab states (27.7 percentage points), and Eastern Asia (21 percentage points).

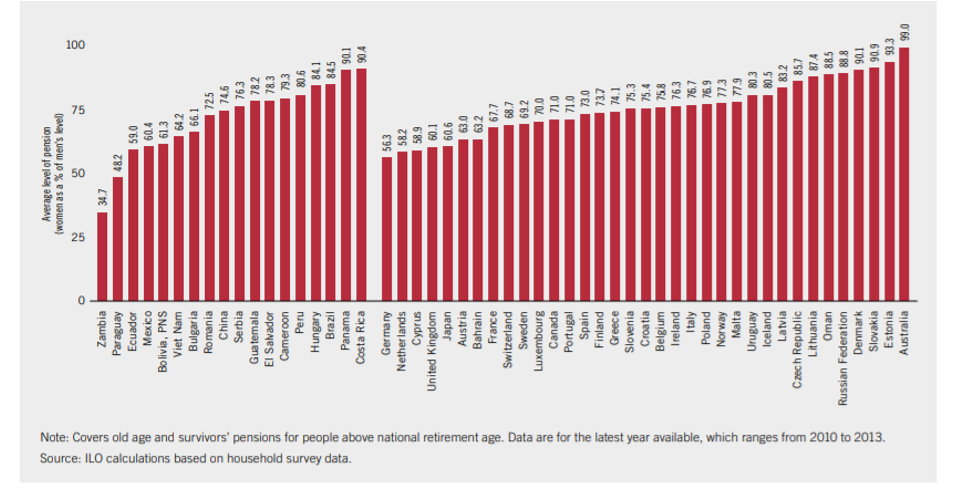

Even when women receive pension benefits, they are systematically lower than pay-outs for men (figure 2). The gap in received pension benefits is a result of numerous interrelated factors. For example, women are less likely to meet baseline contributory requirements and accumulate adequate pension rights when pay-outs are based on formal paid work contributions and systems do not acknowledge interruptions in working life due to caregiving.

Source: ILO, 2016

Universal pension schemes provide a chance to acknowledge women’s contributions to society

The findings from the World Bank’s 1994 Averting the Old Age Crisis report recommended that employment-related pensions were the most effective scheme to ensure poverty reduction in old age in developing countries. These schemes were implemented in many countries. However, they achieved very low coverage because they were restricted to formally employed workers. The lack of successful evidence shows that these schemes exclude large subsets of the population, particularly women who work as homemakers, domestic labourers or within the informal economy. Pensions financed from payroll taxes replicate gender inequalities. Evidence from Bangladesh found that 88% of the employment-related pension scheme recipients were men. By failing to acknowledge that women work fewer years because of their increased societal responsibilities or lack of access to the formal labour market, schemes do not equitably reduce old-age poverty.

In contrast, universal non-contributory pensions financed by general taxation are an effective solution to achieving old age poverty reduction. When evaluating them from a gender perspective, by providing men and women equal pension entitlements irrespective of their formal paid contribution within the labour market, they successfully recognise women’s unpaid societal contributions. It is estimated that over 85% of countries that do not experience a gender gap in pension coverage have non-contributory pension schemes in place, either through universal pensions or pension-tested schemes. Successful universal pension schemes have been established in various developing countries, including Mauritius, Namibia, and Nepal. Contrary to the World Bank’s concern, universal pension schemes have been implemented at a low cost to countries. Estimates from the ILO suggest that even the majority of the world’s poorest countries would be able to afford universal minimum pensions.

Pension systems need to be equitable and redistributive to eliminate gender bias and successfully reduce old-age inequality. Universal coverage would ensure that women are acknowledged for their lifetime contributions to society. They also provide women with increased independence; evidence from Kenya shows that the Inua Jamii universal social pension system provides women with increased feelings of autonomy and self-worth as often, for the first time in their lives, they are provided with regular income on an equal basis with men. Unpaid work needs to stop being invisible; it subordinates women throughout their lives. Universal pension systems provide an opportunity for their societal value to be acknowledged.

About the Author

Darshni Nagaria is studying MSc Development Economics at SOAS. Prior to starting the Masters, she worked as a Senior Analyst in global health research and a Data and Analytics Adviser within the long-term savings and protection industry. She holds a BSc Economics degree from the University of Surrey. Darshni’s interests lie in examining the effects of the financialisation of social policy.