Building a Socially Just Community

Black History Month in the United Kingdom emerged from the declaration of 1987-88 as African Jubilee Year by the former Greater London Council to celebrate 150 years since emancipation, the centenary of the birth of Marcus Garvey and 25 years since the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). The OAU has since become the African Union – but the importance of highlighting the contribution of Africans and Afro-Diasporic communities to the socio-political and economic life of the United Kingdom and the rest of the world remains pertinent today. It follows that highlighting Black people’s contributions does not disappear after October, nor do discussions about Black lives. This Black History Month, I want to reflect on Black liberation at this historical juncture.

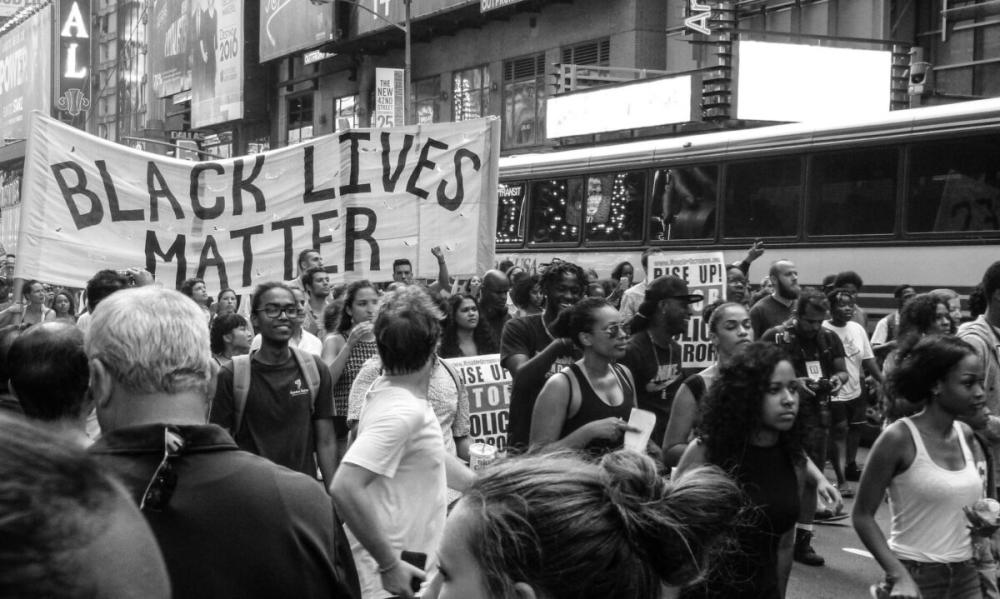

At the height of the global Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the summer of 2020, I was invited to reflect on the resurgence of debates on anti-Blackness. I opted for a conversation with an African colleague of Asian descent working out of Washington DC with a multi-regional feminist movement support organisation. In this article, we spoke about what BLM evoked for us given our geographical and institutional locations. At the same time, a colleague – Sophie Chamas at the Centre for Gender Studies where I was located – invited us to talk about #BlackinTheIvory, a hashtag that coalesced Black faculty experiences in the United States of America. In my estimation, Dr Chamas, a Lebanese scholar, was asking colleagues to resist the reflex to issue broad statements about BLM targeted at the world and instead focus on extending solidarity in real-time at SOAS.

The work of active solidarity can be found in the scandal of Nikole Hannah-Jones, who was denied tenure by the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill for a Knight Chair in Race and Investigative Reporting that came with tenure for all its previous occupants. After a protracted battle that included collective action from staff and students, Professor Hannah-Jones was eventually offered tenure – which she declined and instead accepted an invitation for a tenured Knight Chair at Howard University. Hannah-Jones’ experience is not dissimilar to the experience of academics in the United Kingdom (See Mirza, 2018; Bhopal, 2016; Rollock, 2012)

In these and many other examples, we see the intersecting axes that reproduce exclusion in our societies. The systems and structures that sustain these deeply insidious forms of racism are networked and make them difficult to identify. It is this insidiousness that Valerie Amos highlighted when she drew comparisons between her generation in Britain of the 1960s and 70s and the myth of “work hard and you will succeed”, versus the frustration of the younger generation today who refuse to be sold “all you need is education and hard work”. After all, it is not too long ago that Black Caribbean children in Britain were overrepresented in schools for the so-called “educationally subnormal”. These young children were characterised as slower because of poorer concentration and language problems in a country they were adjusting to. That the education system is hardwired to create and reproduce exclusions for Black children is a fact we cannot run away from in 2021 given disparities in awarding gaps for Black students in universities.

In addition, the younger generation is coming of age in an increasingly hostile national and global environment in which ethno-nationalist politics have found a greater and bolder footing in formal political spaces and universities. This environment produces real threats for racialised “others” and we do not need to look too far for an example given Lisa Tilley’s decision to resign from her job at Birkbeck University. Between debates on academic freedom, freedom of speech, and racism denialism, we are in a complex terrain with real material risks for all of us. Consequently, how we approach what we assume to be a commitment among a sufficient majority to shift racial inequalities whilst concomitantly addressing the intersections from which other forms of exclusions arise, becomes a careful balancing act. There are three points I would like to conclude on, noting that each could merit a fuller exploration on its own.

The classroom as a site of transformation

As a feminist scholar, I spend time thinking about the purpose of the classroom and the conditions we create for learning, unlearning, and respect without refusing or compromising the need for difficult conversations. If we are doing education right, then the classroom is always an uncomfortable space because long-held viewpoints are constantly challenged. As I have argued here, a conversation about patriarchy need not descend into “not all men” if we recognise that we are talking about structures of power and not individuals. Similarly, conversations about race and anti-Blackness need not descend into “all lives matter” because that sidesteps a structural analysis of how race and racialisation is produced and experienced.

As pedagogues and facilitators of knowledge transfer, there is careful work required to create learning spaces that are not only generative and intellectually rigorous, but which do not also mobilise “plurality of views” to sustain racist, sexist and classist viewpoints. There is a level of pedagogical astuteness that is needed to navigate a learning environment that does not leave the students with “here is the evidence, make of it what you will”. As educators, we have a responsibility to build inclusive and brave classrooms that centre the fundamental principle of the academic enterprise – breadth and depth of evidence on a topic. We should challenge any resistance to critical, inter, and transdisciplinary scholarship based on disciplinary fidelity or a reluctance to extend oneself beyond that which they are familiar.

The university as a created community

Most of us arrive here not knowing each other, which means we are unlikely to agree on everything. In fact, it is unlikely that many will ever agree to change. It is uncomfortable and involves redistributing power. However, we can develop sufficient consensus that we have a responsibility to not cause harm when we disagree. One such debate on which we must agree to not cause harm is the value and utility of autonomous or safe spaces on campuses. There are vibrant debates about safe spaces in US universities. Autonomous or safe spaces emerge from a range of political movements – civil rights, feminist, and queer movements – as autonomous spaces for political organising and strategy building. In universities, safe spaces, outside the classroom, remain important for building community among groups that feel isolated, threatened, or underserved because they are a minority. Autonomous spaces are not a tactic of exclusion, they are a strategy for survival and community building. To respect and value these spaces is to understand the depth of racial, gender, and class-based harms in our societies. Autonomous spaces can exist alongside collective spaces for coalition building.

Coalition and building a socially just community

Finally, I want to speak to our theory of liberation and the role of coalition-building among many other strategies for building a socially just community. What work is required? Is it organising across movements or one individual at a time? Is it statements and motions? Is it work within autonomous spaces? Is it direct action or behind the scenes institutional work? Does change require bold, imaginative, and disruptive actions? Is it all these things? I think so. In fact, at different moments of my life, I have engaged in one form or another of the actions above. However, if we agree that one size does not fit all and alliances at one point or another are important, then what kind of alliances do we need to build and how? I come from a generation of organisers who believed in working within the movements we built. We understood our collective mission and we found rejuvenation in a context in which feminist objectives were viewed as a distraction and a “western” agenda. The African Feminist Forum remains a pivotal space in this regard.

However, as I grew older, I developed an appreciation for working across movements. Likewise, the task of building racially just worlds that confront anti-Blackness head on rather than obscure it requires building effective coalitions. Being an ally demands the hard work of challenging communities and occupying spaces we neither have the time nor reserves to engage. It is the task of speaking and working against racism. Yet, if we are to build effective coalitions, we should be able to challenge each other with empathy, compassion, and respect based on the understanding that we have a shared collective mission. No one wants an ally who watches you walk into a hole and says, “well, I am not Black, so I didn’t think I could tell you that is a hole, you are headed for it, and you will break your neck.”

Real allyship requires that we create the conditions for disagreements and differences to be viewed as productive engagements. There are differentiated responsibilities in collective struggles. Acknowledging and working through these differentiated responsibilities requires a commitment to doing the work. We live in a world where the word ‘racism’ or ‘anti-Blackness’ invokes discomfort in most people who do not experience racial harms against Black people, or even amongst Black people who see anti-Blackness as something that affects individuals rather than a structural issue. “This is divisive, I am not the problem, I am not racist”. The next time you feel a tinge of discomfort, take it as an invitation to interrogate why “after all these years”, we still need to have this conversation. If you are reflexive, the evidence is always around you.

Dr Awino Okech is a Reader in Political Sociology and Associate Director Equity and Accountability at SOAS University of London.